Questions & Answers

with Chris Haughton

In Chris Haughton’s fascinating new book, The History of Information — published by DK and soon to come out in twelve foreign languages — the author traces the story of mankind to show how humanity’s most significant innovations came to be thanks to the sharing and storing of information. We’ve asked Chris seven questions to give readers a better understanding of the book and his reasons for writing it.

If you are interested in receiving our newsletter, with interviews and many other insights, click here.

DBA: You’re best known for your best-selling picture books for toddlers. How has your experience as a picture book creator informed the making of The History of Information?

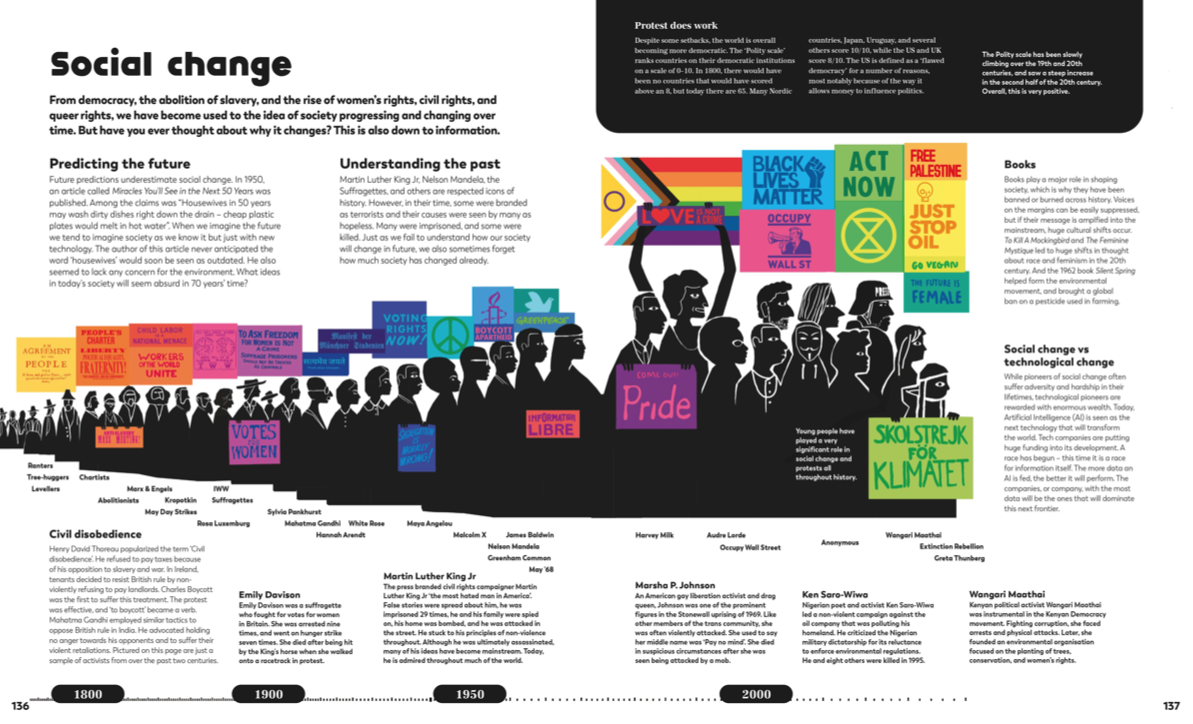

CH: I think they are both very similar really. I actually never felt comfortable as an author but I had confidence in my illustration ability. I had a realisation when working out my first book that I didn’t have to rely on words. I could tell stories through pictures. And really I think this is the key to their success: they translate well to other languages and most importantly they communicate to young children. This non-fiction book also tells a story through pictures. I see The History of Information as a visual timeline of graphics: from prehistoric cave art to hieroglyphs to social media and AI. The endpapers in some way encapsulate this. They are a visual timeline of one icon: the arrow. They begin with a prehistoric arrow and show arrows as they came to be used throughout history.

What compelled you to write and illustrate The History of Information?

I had the idea for this book in 2006, long before I wrote any of my picture books. I was listening to some lectures from UC Berkeley. One of the courses was called 'The History of Information'. It followed the history of information technology: IT, computers, internet and AI. But it did this by taking a very wide view of the technologies. Drawing is an information technology. So is writing. All communication is.

What kept you at it for 17 years?

I was just really interested in it. It was a completely different way of looking at the world. Seeing society as an information network is, I think, a really eye opening way of looking at history. It explains so much, rather than seeing history as a series of events of kings and queens, it helps to explain why.

The story also has a visual element to it which I thought I could show. The book is really a history of graphics told through graphics. We don’t often think about it like this but graphics dominate culture. Today our world is dominated by graphical user interfaces: if we buy something, order a taxi, book a hotel, train, flight we often do these things through GUI icons. Even if we are just communicating with friends, we often do so through a screen. Messages, likes, shares, retweets. I’m writing this through a screen and you are probably reading it through one. But this is nothing new, graphics have always lead society. For thousands of years another graphical interface dominated society: the written word.

How has information changed in the time that it took you to write this book?

The course was written in 2006, so there's been a huge amount of change in our media since then. It was the very beginning of social media. Facebook was only launched in 2005. Social media has followed the same pattern as previous information technologies have. When radio became popular in the 1920s it was pioneered by hobbyists who had this utopian idea of sharing information and playing music for free. But soon commercial pressures began affecting radio hobbyists. They either went pro or shut down. That same process happened with the internet startups. Advertising crept in and with it engagement targets, click bait and all the rest of it.

What advice about information — or disinformation — would you give to a person coming of age today?

Contrary to what many people believe our ‘free’ press is not at all free. There are and have always been elements of disinformation mixed in with the information in all our media. Wherever there is information there is disinformation. Everyone, everywhere is tempted to twist the facts.

We need to realise that the vast majority of media outlets are not public service. They are businesses. They will only write stories that will help their business. If a story is too critical of the government or its advertisers it will cause problems for the owners. If it compromises the viability of the business the story will not run.

Question sources: Always check the source of the information and think about who is writing it and why.

Cross-verify: Compare information from multiple sources. If there is a conflict, such as a war, the news from both sides is always, always biased. There will almost certainly be unreliable claims and disinformation mixed in with the facts. Seek out the news from both sides of the conflict, from the original words of the people and politicians and newspapers on the enemy side. And from media in other countries not involved in the conflict. What are the newspapers on the other sides saying? You need to take a look at these before you can hope to get a clear picture about what is really going on.

Analyse content: Look out for sensationalist headlines, lack of evidence, or emotional manipulation. What words are they choosing to use? And why?

Who is this book for?

I think it’s for everyone. I wanted to make a book that explains media studies to a wider audience. I studied media studies in college but only after I graduated did I realise just how important a subject it is. I also realised that most people are completely unaware of how manipulative the media really is. In particular I wanted to highlight Noam Chomsky’s work. We have made the language in the book as accessible as possible so that even children can understand it, but really my aim was for adults to read it. If you read it from cover to cover I think it leads to some quite profound, core ideas about society. I think it subverts some of the assumptions that we in the Western world have of ourselves.

Among the book’s many takeaways, which one is the most important to you?

I think it would be this conflict between information and disinformation. In a way it’s like an arms race. It is sometimes argued that the reason our brains enlarged over the last few million years is down to trying to figure out these deceptions between each other.